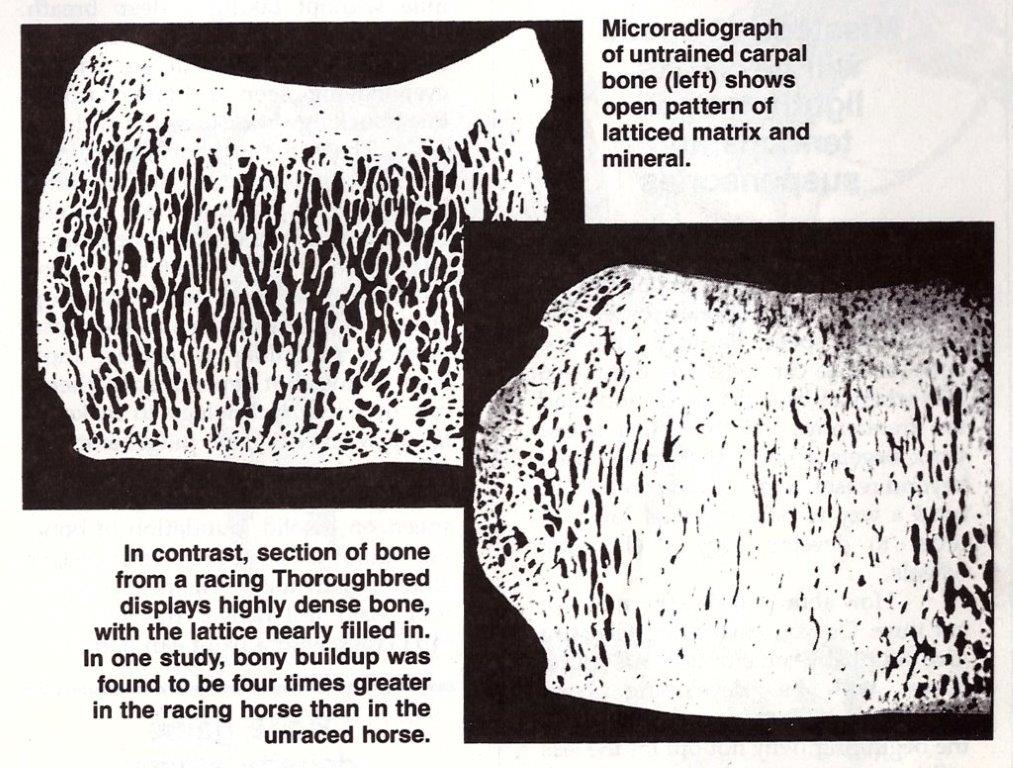

Radiographs of equine carpal bones

The way we train our racehorses today is dead wrong, economically as well as physiologically. We consider a two mile gallop a marathon, three miles impossible. We’ve spoiled our exercise riders to the point where they simply won’t deliver mileage, won’t stay on the track with a horse for more than 10 minutes. We are seduced time after time, horse after horse, into developing speed – the easiest commodity – immediately, long before any part of the horse is ready for it. Then we attempt to wring stamina from our turnip during competition.

The winners are simply the survivors, and how often does the entire field stagger home on its knees? One need only look at a few basic principles of biology to see that our conditioning methods are just plain outdated, and a tremendous disservice to the horse itself.

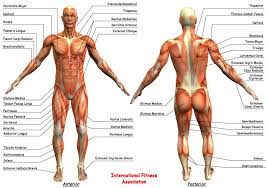

A bone is a living, plastic substance, changing dramatically depending on the stimuli it receives from the environment. This fact should be quite encouraging to the conditioners of equine athletes because it means that, with proper training, the incidence of chipped bones, bucked shins and joint-disease can be substantially reduced, even if the animal is not perfectly conformed. But what kind of conditioning is best for the young horse?

Human, as well as recent equine sports medicine studies show that bone quickly increases in density (and thus strength) with the stimulus of just a few high concussion loads, in periodic exercise sessions. In other words, if you want your baby’s bones to become hard and strong in the quickest way, then he should regularly sprint short distances – just like he does running free in the paddock. We’re led to conclude then, that once the baby goes under the saddle (say, for race training) he should continue to experience short fast bursts to ensure the development of strong bones.

As tradition has it, most thoroughbred babies see short, near-maximal bursts of speed very early in their training regime – perhaps as soon as 60 days after they go into training. Just what the doctor ordered.

But why then are young racehorses in training chipping bones, bucking shins and destroying joints by the thousands? It would appear that we’re doing exactly as the scientists suggest, except that they might bring on the speed even earlier, and deliver more of it. Is theirs a prescription for salvation, or a recipe for disaster?

Let’s revisit the studies. Essentially the findings are as follows: the horse standing still or simply grazing all day gradually develops stronger bones, but nowhere near as quickly or as strong as those horses that sprint at near-maximum speed over short distances. And horses that gallop long distances develop strong bones much faster than those standing still, but not nearly as fast as the sprinters. The studies, because of limited funding, generally have lasted for periods of six weeks to four months, and have not been performed on stock with actual racing potential.

IF we put the speed theory into practice with our baby racing prospects, we might begin with a week or two of getting the youngster used to the track. Perhaps a week of half-mile trot, followed by a half-mile of hobby horse canter leading to a second week of a daily full-mile of easy canter. At this point, or after a month of one to one and a half miles of daily galloping we’d begin our short sprints.

If you’re a horseman you know what’s going to happen. Once the baby gets his legs untangled he’s going to love the speed – just what he was bred for! A little 100-yard squirt each day. Wow, what fun! In a week he’ll be jumping out of his skin waiting for those five seconds of total freedom, and he’ll be getting hard to stop. In a month, the sprints will be quarters in :24, then three-eights in :37. And that, my friend, is too fast, too soon.

The racehorse is like a racing car with two gears: jog and GO! It’s very difficult to persuade a sprint trained racehorse to lope at a rate of 3:00 a mile, then gallop out a notch at 2:45, and another at 2:30. If the horse has already met sub-2-minute-mile speed, the next gear after job is tally ho. In contrast, the eventing horse, which has experienced hours a day under the saddle, at all rates of speed, performing a variety of skills on command, can become a rateable, push-button animal over time. Even so, give this extremely fit and well-trained animal a week of short sprints and he’ll become Godzilla II.

Meanwhile tendons and ligaments, which develop strength through repeated stretchings, tens of thousands of flexings, are left behind. Juvenile legs need time and practice to become smart and error-free. Missteps at speed will devastate lightly trained tendons and suspensories.

So we’ve got a problem. We want good, solid bone under our horse, and speed develops the best bone exercise can produce. But speed kills when it’s brought on too soon and too frequently, and too much speed work begets a horse that loves speed beyond reason and beyond control. We need a way to deliver speed safely in order to develop solid steel racing wheels.

How about a little at a time? I’ve got time. Do you have time? Can you give your baby some time? Your young horse will be developing bone throughout its first year of training. In the beginning, why not opt for the less efficient – but far safer – stimulus of mileage rather than speed? Why not develop bone at a more physiologically acceptable pace while strengthening tendons and ligaments and thickening protective cartilage pads – the other hard tissue, and the slowest to respond?

Bones don’t snap outside the context of the connective tissues that support them. Sure, bones are the obvious victims of an ill-advised training programme, but they are only the captives of the tendons, ligaments and other fascia which toughen and harden no sooner than thousands of repeated stretchings and flexing during the long slow distance (LSD) phase of training.

Ant there is another catch to speed work: every fast work weakens bone. It takes bone seven to ten days to recover and remodel from a speed workout. Without this rebound time, bone becomes progressively weaker, not stronger, and approaches mechanical failure. In addition, bone gains density slowly and loses it relatively quickly – just the reverse of the horse’s energy delivery system. You might think he’s ready to conquer the world after a two to three week lay-off due to an illness, but his bones might be set up for a catastrophic breakdown.

So sneak up on speed. Start out long and slow and end up, six to nine months later, short and fast. Three minute miles can become 2:30 miles, then 2:00 miles, developing cardiovascular fitness and increasing muscle oxygen uptake for sustained high speed – before high speed bouts are introduced.

And finally, after all the groundwork is done, you can point your iron kid at the kind of all-out effort the scientists say develops maximal bone strength. The speed your horse is built to maintain for 5/8ths of a mile without taking a deep breath. Speed he can maintain for a mile and beyond. Speed he can deliver without ever having seen a bone-chipping, knee-bucking, hock-popping furlong.

That’s the logic of conditioning the flesh-and-blood racing machine. It’s a program that respects and builds on nature’s physiological timetables of adaptation, both metabolic and mechanical. It understands the properties of living systems and the consequences of failing to respect those laws. It does not depend upon chemicals or tricky technology to make up for impatience or poor judgement. It is always moving forward, asking a little more, but never in a hurry, building speed on a solid foundation of bone. The goal is a sound, enthusiastic athlete, ready for the rigors of competition. And it’ll deliver the bone you can’t crack with a ball-peen hammer.

That’s the kind of bone that will carry your equine athlete through a career that lasts more than one season, or one race.

(Source: Tom Ivers)

Further reading: Dr Deb Bennett’s Ranger Piece

‹ Previous